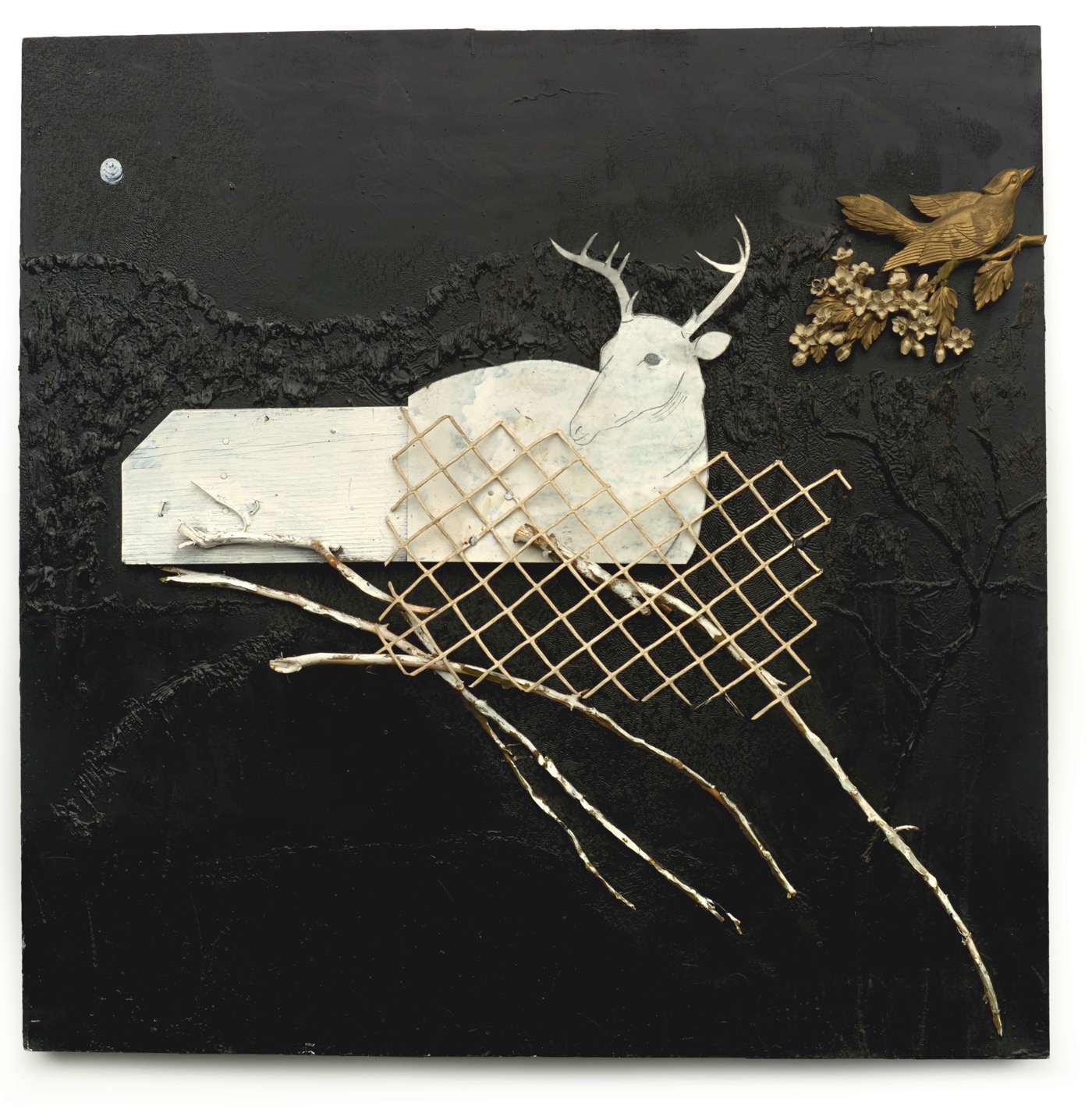

Ronald

Lockett, “Rebirth” (1987), wire, nails, and paint on Masonite, 12 x 18

1/2 x 1 1/2 in, collection of Souls Grown Deep Foundation (all photos by

Stephen Pitkin / Pitkin Studio)

Ronald Lockett believed in magic. So said sculptor

Kevin Sampson during a talk in July at the American Folk Art Museum (AFAM), which is currently hosting a

retrospective of Lockett’s work.

The artist died in 1998 of AIDS-related pneumonia, so hearing Sampson

say that Lockett believed that the objects he made with his hands had

power beyond aesthetic allure makes sense. Being black and gay and male

in the rural South — Bessemer, Alabama — one would have to stay under

the radar, or, as Sampson put it, “keep to himself.”

But this may not be true. According the biographical essay by collector Paul Arnett on the website of

Souls Grown Deep (his nonprofit foundation

promoting many

self-taught artists from the South),

Lockett’s sexuality was questioned by many, and he had female sexual

partners. See? I’ve already tumbled into the well of personal narrative

that makes Lockett’s art eddy into a whirlpool of sentimentality, pity,

and rage about the shrunken life chances of people like Lockett from the

rural South, people who graduated from high school, but never learned a

trade and who lived in their mother’s house their entire lives. This is

the tension pulled taught by the contravening forces of the work, which

has its own things to say, and the story of his life, and also the

category in which we place Lockett. Is he a vernacular artist, or a

craft artist; an outsider artist, or one who is self-taught? In this

context, it feels unfair to say he died of “AIDS-related pneumonia.” I

have to say “AIDS-related pneumonia at age 32” because this is true and a

key part of his story, but I also need to put that aside for a moment

to talk about his artwork.

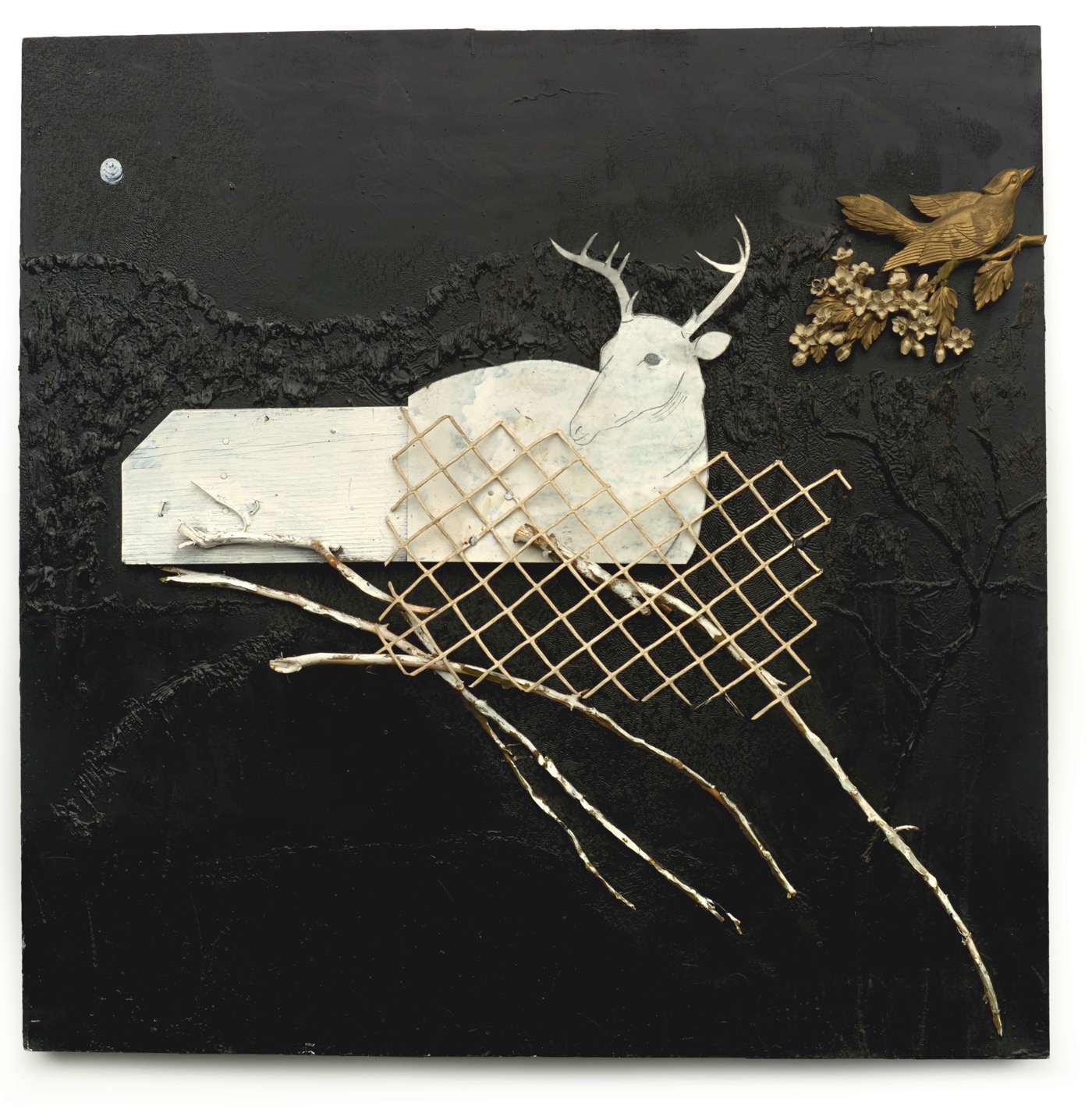

Ronald

Lockett, “Traps (Golden Bird)” (1990), chain-link fencing, branches,

cut tin, industrial sealing compound, and found plastic bird and

berries, 48 x 48 x 4 in, collection of Tinwood LLC

Lockett takes some of the strategies I am familiar with, but imbues

them with — there’s no other way to accurately say it — heart. Look at “

Holocaust”

(1988). He separates the story of that historic horror with two

separate fields of color that then become the story and the

meta-discursive comment on it. White skeletal bodies made of painted

metal are tossed willy-nilly into the air of an utterly black setting

and then, on the right side of the piece, demarcated by a change in

color scheme, just green on the bottom and blue on top as if a new day

had dawned. You can also see him reworking ideas in this show. “Rebirth”

(1987) features a skeletal dog in painted tin that’s stark white on a

black background and, to the right, another field of green grass, but

this time bloodstained under a washy blue sky. Lockett has an

intelligence with materiality and with drama that together make things

matter, even if the history isn’t completely familiar. The revelations

continue as you walk through the show. “

Sacrifice”

(1987) consists of a shelf of wood with a painted figure made of

wire — a lone figure on a cross, clearly meant to refer to Christ,

delineated from the cross itself by the use of white paint. The figure

is both part of the structure and floating above it.

Ronald Lockett, “Homeless People” (1989), paint and wood on fiberboard, 48 x 48 1/4 x 1 1/2 in, collection of Ron and June Shelp

In the exhibition

Fever Within: The Art of Ronald Lockett,

AFAM wants you to see the magic that Lockett supposedly believed in and

brought to bear on nails, tin, tree branches, chicken wire, industrial

sealing compound, plastic vents, charred wood, and the enamel and paint

he could hardly afford at times. But is there any other way to talk

about these works and convey Lockett’s spirit except by using terms like

“magic”? It’s alchemy to change the basic ingredients that went into

his artist’s cauldron into works of staggering feeling.

Ronald

Lockett, “Fever Within” (1995), tin, colored pencil, and nails on wood,

66 1/2 x 30 x 2 in, collection of Souls Grown Deep Foundation (click to

enlarge)

This exhibition asks you to do more work than most museum shows. Not

only do you need to decide how to feel about the transformations Lockett

accomplished, you also have to decide how to divide your

attention between his story and his work. AFAM complicates this choice

by simultaneously running the exhibition

Once Something Has Lived It Can Never Really Die in

an adjacent hall, where Lockett’s work is paired with votive symbols

and indigenous crafts of various tribes to make the point that this work

has a performative aspect. It’s about calling forth another reality

that the maker wants — perhaps needs — to experience in order to keep

going in this one. Lockett says in a video housed in that second show,

that when he loses himself he goes back to the work to “regain himself.”

It’s awful to think he had nothing else but the objects made from his

own hands to comfort him, but then you are astounded by a painting like “

Civil Rights Marchers” (1988), with all its vicious, ugly swirls of red, black, and white, like blood leavening our entrenched racial antagonism.

All of these generative tensions make Lockett’s work worth seeing and

spending time with. But don’t pity him; there’s no need. You’ll find

Lockett’s hand working tin, wood, iron nails, and paint, working

from deep desire for a conjuring that is its own healing salve.

Ronald Lockett “Untitled (Horse)” (ca 1987), paint on wood with cut tin and nails, 41 x 58 x 3 in, collection of Tinwood LLC

Fever Within: The Art of Ronald Lockett and Once Something Has Lived It Can Never Really Die continue at the American Folk Art Museum (2 Lincoln Square, Upper West Side, Manhattan) through September 18.

No comments:

Post a Comment