Chris Doyle, “Everhigher” (2015) at Andrew Edlin Gallery (all photos by the author for Hyperallergic) (click to enlarge)

At Edlin, the first work visitors will see — indeed, it’s such a gripping sight through the gallery’s glass façade that it probably compels countless passersby to come in — is Saya Woolfalk‘s sci-fi installation “ChimaTEK: Future Relic” (2015). But with no explanation on hand about the post-apocalyptic cosmology informing the artist’s aesthetic, the piece’s environmental message may not come across. Lining the gallery’s long hallway is Peter Fend‘s “Olya” (2015), a scale rendering of a submarine designed to convert the plastic particles floating in earth’s oceans into energy with text explaining how the sub will herald a new global economy based on recycling. It suffers from the opposite problem of Woolfalk’s work: too much explanation and too little to look at.

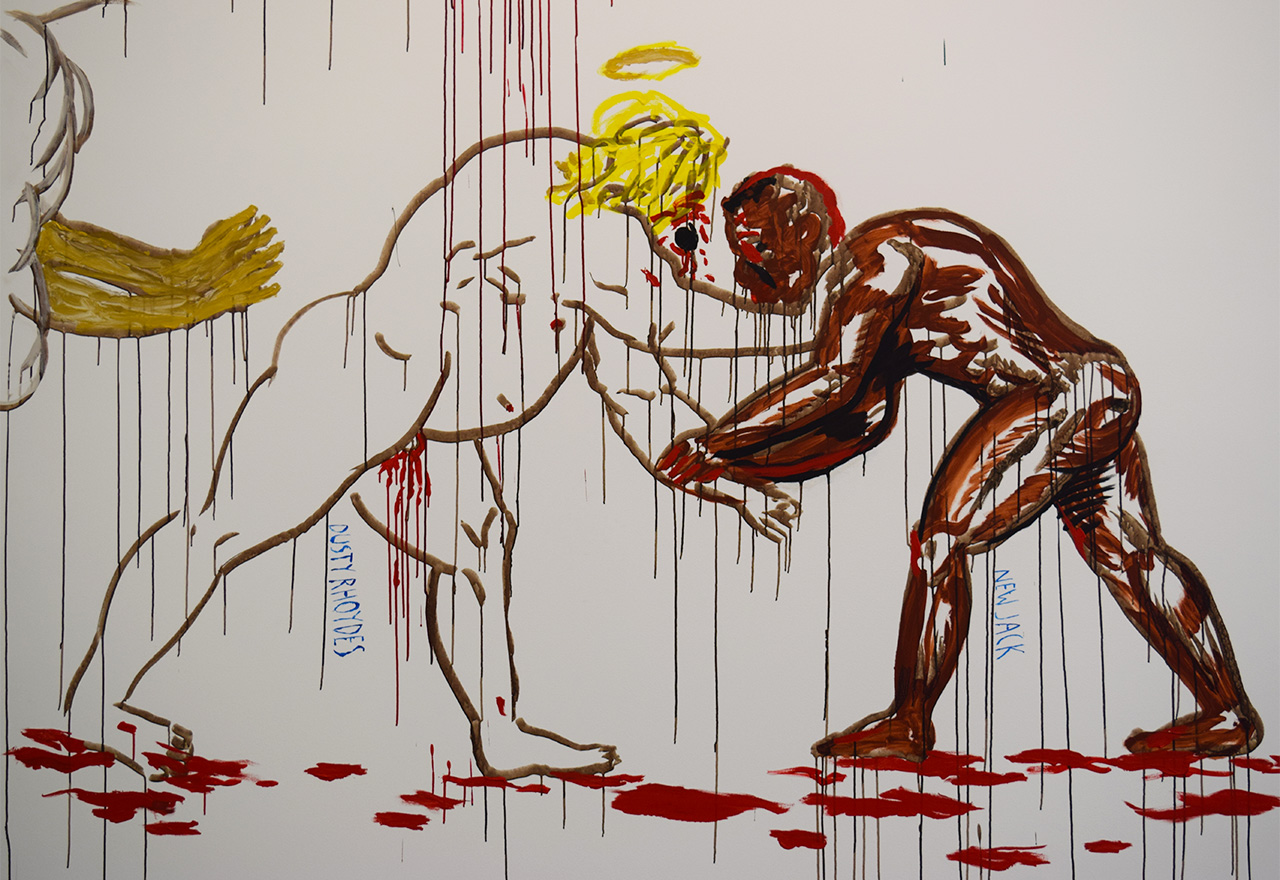

The gallery’s back room is the real draw here, especially the three enormous murals by Kevin Sampson, Brian Adam Douglas, and Chris Doyle. (A fourth, “Present Tense” by Rigo 23, is a capable infographic listing the eight countries that still don’t have mandatory paid maternity leave, the largest being the United States.) Douglas and Doyle both imagine epic flood scenes. The former’s piece, “The Rain Dogs” (2015), is characteristically surreal, rendered entirely in black, white, and gray, and reminiscent of the photos of devastation wrought by hurricanes Sandy and Katrina. Doyle’s polychrome painting, “Everhigher” (2015), features a sci-fi metropolis that is either a city-sized water park, or in the midst of a devastating flood. At the center of the composition, a statue resembling Vladimir Lenin stands atop a water slide in the shape of a coiled dragon.

Detail of Kevin Sampson, “Fruit of the Poisonus Tree” (2015) at Andrew Edlin Gallery (click to enlarge)

Almost any mural would look safe and subdued by comparison, and the works at Gladstone are no exception. That said, a few pieces in Hello Walls do make a strong impression. Amid the summery fodder at the gallery’s 21st Street space — the sunny rings of Ugo Rondinone’s “vierterjunizweitausendundfünfzehn” (2015), the orange and blue splatter of Arturo Herrera’s “Come Again” (2015) — Raymond Pettibon’s “No Title (Arts and letters…)” (2015) is full of manic energy and strange, disjointed imagery. At the core of the piece, which includes Johnny Rotten fellating a satanic unicorn and a father-son wrestler duo sparring, is a half-formed idea about the breeding of athletic talent and sporting dynasties. The enigmatic result is by far the most compelling piece in Gladstone’s 21st Street building.

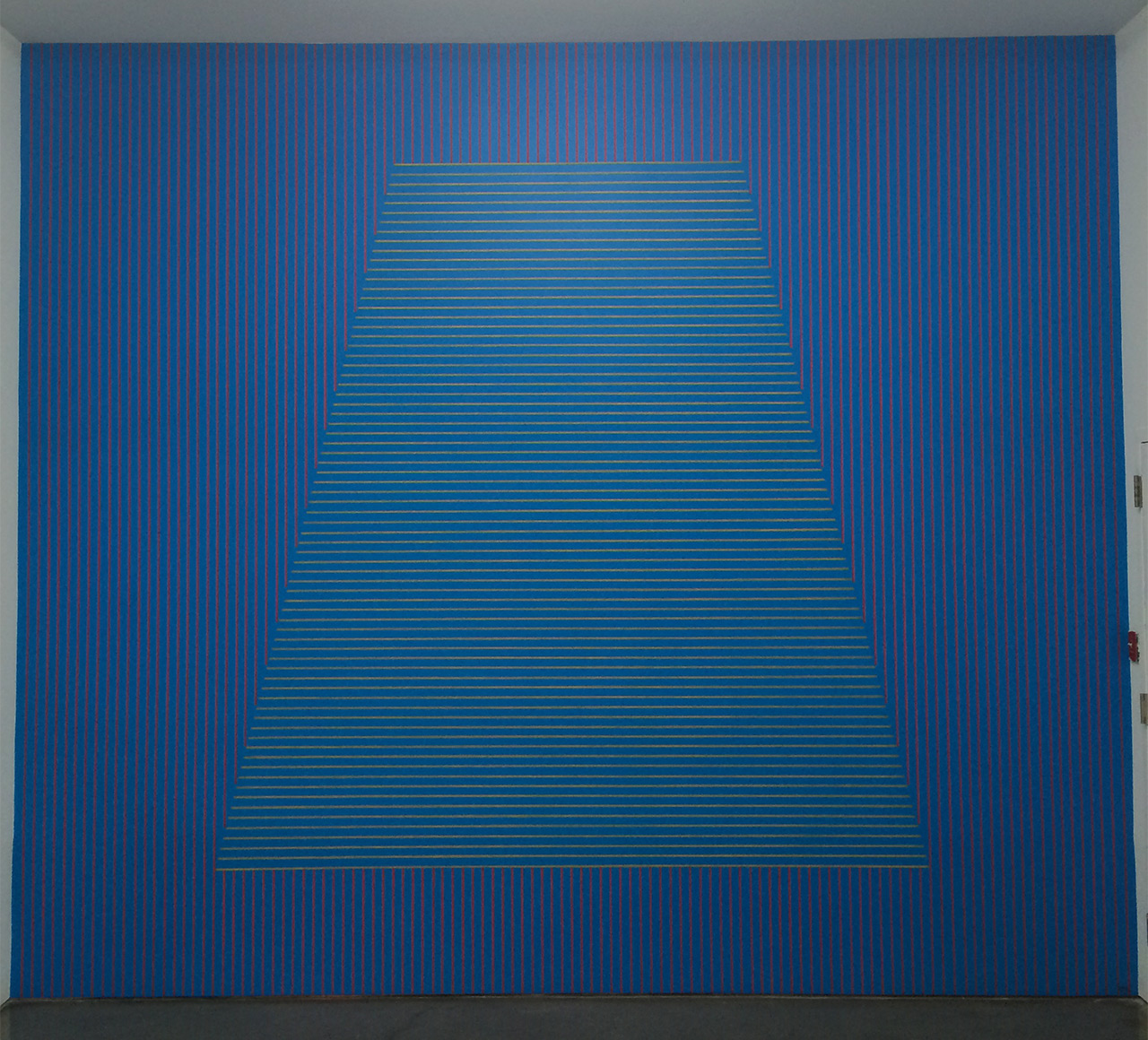

On 24th Street, things are not much different, and it’s Wangechi Mutu‘s “A planet full of Snakes” (2015) that stands above the rest. (Although a Sol LeWitt wall drawing from 1980 unexpectedly emerges as Hello Walls‘s most seasonally appropriate work, its trapezoid of yellow lines on a blue and red backdrop looking alternately like a pier jutting into the ocean or a beach towel spread on the sand.) Even Kara Walker‘s wall piece “Auntie Walker’s Wall Sampler for Civilians” (2013), though it’s the only explicitly political work on view at Gladstone, reads like a recap, or, true to its title, a sampler. Mutu’s mural, meanwhile, features an orb of collaged snake bodies with no heads — some of which seem to be spouting blood — and motorcycle parts. The rest of the wall is scattered with disembodied snake heads, their neck stumps marked with splatters of crimson paint. This scene of interstellar reptile genocide makes nearby murals by Daniel Buren, Jeff Elrod, Karl Holmqvist, Neil Campbell, and others look painfully dull. The only thing that could make Mutu’s contribution better is if she had given the piece the seemingly obvious pun title “Snakes on a Planet.”

The contrast between Hello Walls and Anthems for the Mother Earth Goddess may simply be the product of having been produced by two very different galleries. Nevertheless, it’s thrilling how politically engaged and elaborate the murals at Edlin are, while those at Gladstone offer a more purely visual kind of satisfaction from their formal experiments with color, texture, and imagery. The scant overlap between the two makes for interesting comparisons — or, at least, an enjoyable summer aesthetic fling.

Detail of Chris Doyle, “Everhigher” (2015) at Andrew Edlin Gallery

Ugo Rondinone, “vierterjunizweitausendundfünfzehn” (2015) at Gladstone Gallery

Arturo Herrera, “Come Again” (2015, left) and Michael Craig-Martin, “To Go” (2015, right) at Gladstone Gallery

Detail of Raymond Pettibon, “No Title (Arts and letters…)” (2015) at Gladstone Gallery

Lawrence

Weiner, “LANGUAGE + THE MATERIAL REFERRED TO” (2010, left), Kara

Walker, “Auntie Walker’s Wall Sampler for Civilians” (2013, right) at

Gladstone Gallery (click to enlarge)

Detail of Wangechi Mutu, “A planet full of Snakes” (2015) at Gladstone Gallery

Sol

LeWitt, “#333: On a blue wall, red vertical parallel lines, and in the

center of the wall, a trapezoid within which are yellow horizontal

parallel lines. The vertical lines do not enter the figure” (May 1980)

at Gladstone Gallery

Hello Walls continues at Gladstone Gallery (530 West 21st Street and 515 West 24th Street, Chelsea, Manhattan) through July 31.